Auspicious Vultures in the Dark Sky

Feature image by Pierre Dalous CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The first rains to follow the sweltering heat of summer in the desert (al-hamim) fell during the season called al-kharif. For many tribes of Arabia, the year consisted of six seasons of varying length, and the kharif was the last of these. It was called kharif because it was the time when people plucked (kharafa) dates and other kinds of fruit from their trees.

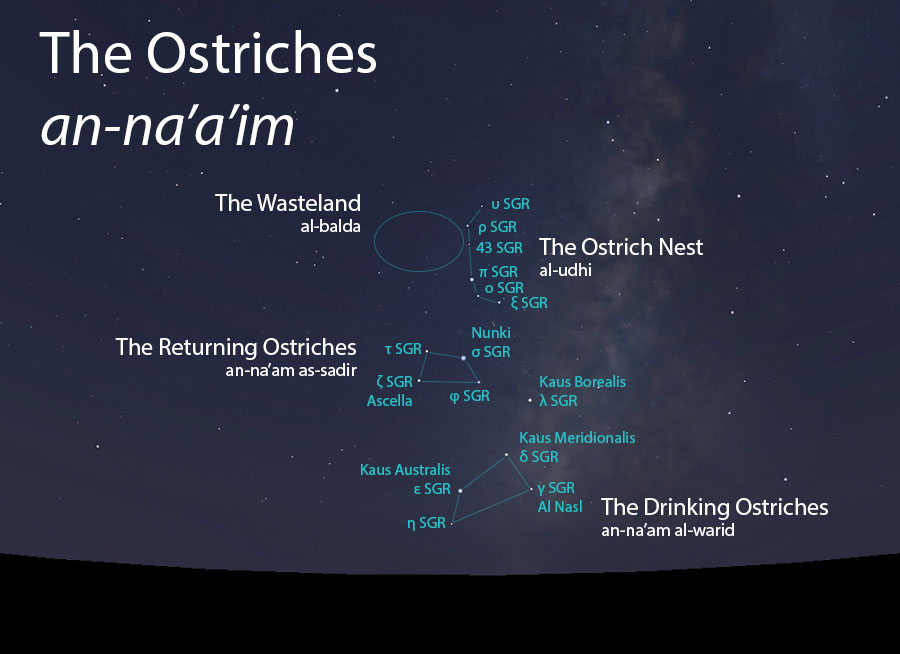

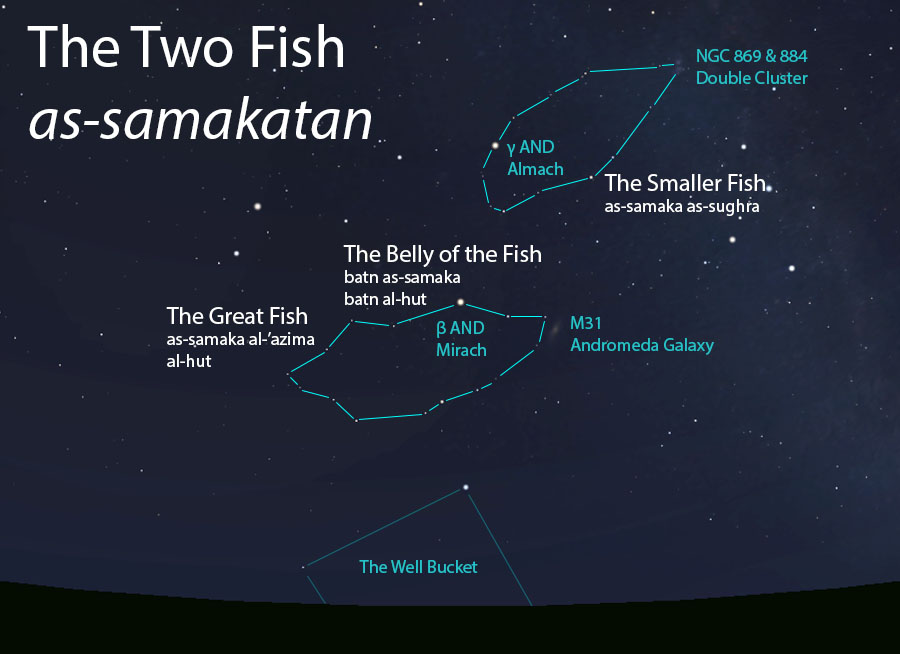

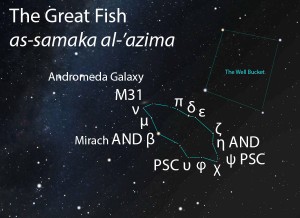

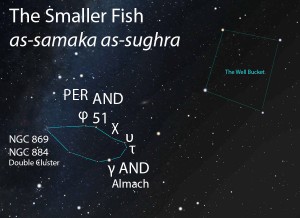

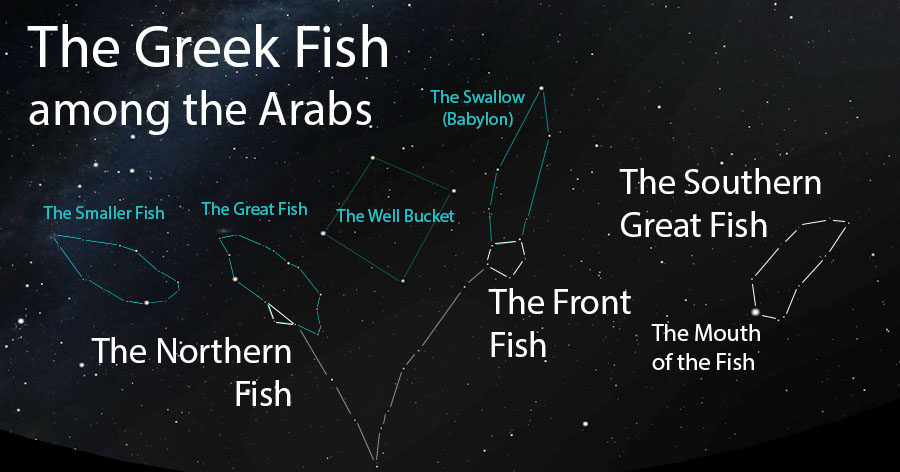

The season begins with the setting of the Two Vultures (an-nasran), according to the rain star calendar of Qushayr. At the same time, the first of ten Auspicious Asterisms (as-su’ud) begins to set, four of which complete the calendar of the lunar stations. Having diverged when the summer began, these two calendars come back together as the autumnal season of fruit harvest (al-kharif) concludes with the setting of the First Spout (al-fargh al-awal) of the Well Bucket (ad-dalw). This brings us full circle to our starting point a year ago.

ظعائن شمن قريح الخريف من الفرغ والأنجم الذابحة

The women traveling in camel litters

directed their gaze to see where the first rain

of the autumnal season of fruit harvest

would descend from the clouds,

the first rain from the Spout

and the stars of the Slaughterer.

At-Tirimah

743 C.E.

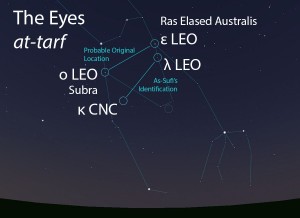

How to observe the Two Vultures

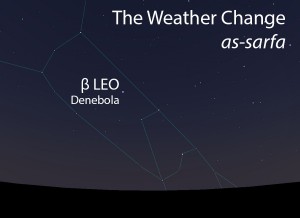

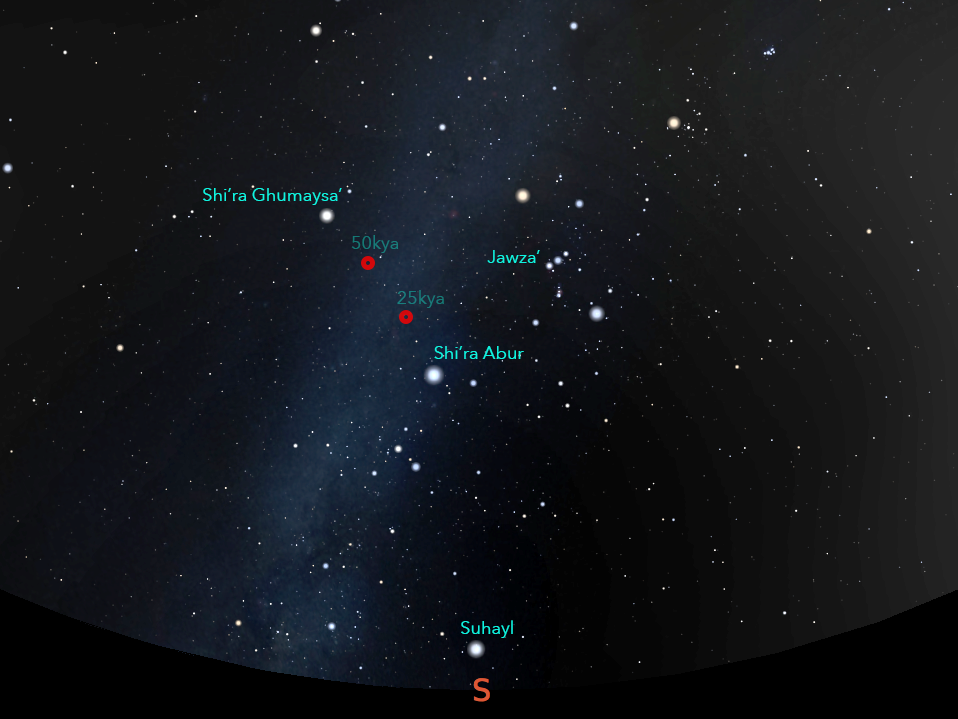

The Two Vultures (an-nasran) as they appear setting in the west about 45 minutes before sunrise in mid-August. Sky simulations made with Stellarium.

The proper time to observe a star’s morning setting (or rising) is called ghalas in Arabic, a time when the darkness of night mixes with the white and red light of dawn in the tracts of the horizon (How to Observe). Look to the western horizon about 45 minutes before your local sunrise (times available at timeanddate.com). You can spot the Two Vultures as a pair of very bright stars spaced widely apart just above the west-northwestern horizon. The one on the left was called the Flying Vulture (an-nasr at-ta’ir) because the two dimmer stars on each side were seen as its outstretched wings. The one on the right was called the Alighting Vulture (an-nasr al-waqi’) because its two closest stars created a V-shaped formation with the bright star, as if the bird had its wings contracted while descending from the sky.

The Two Vultures and the Dark Green as rain stars

For a brief description of the rain stars, please see the Celestial Complexes section on the About page.

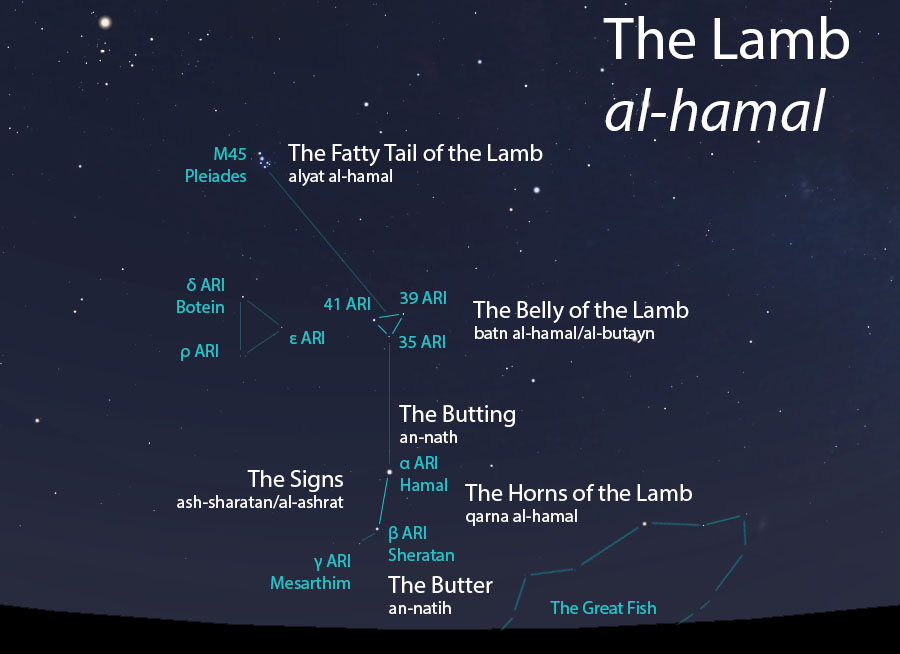

The rainy season of fruit harvest began with the setting of the Two Vultures (an-nasran). In modern-day Arabic, the term nasr more commonly indicates an eagle, but this was less common long ago. Back then, nasr designated a class of large birds known for plucking flesh with the curved ends of their otherwise flat beaks. These vultures were distinguished from the eagle (al-‘uqab) in part by their toes that terminated in large hooked claws rather than fully curved talons. The Egyptians revered the vulture for its utility in eliminating decaying animals, and the Arabs similarly regarded them favorably.

The two bright stars that marked the bodies of the Two Vultures set together along the west-northwestern horizon. Their positions far away from the path of the Moon through the sky (the ecliptic) excluded them from being considered as lunar stations. Nevertheless, these asterisms were highly regarded and were included in the rain star calendar of Qushayr to designate the beginning of the autumnal season of fruit harvest.

Following the setting of the Two Vultures, the rain star calendar of Qushayr mentions a star called the Dark Green (al-akhdar) as the second rain star of the kharif. The identification of this star in the sky is uncertain, but we know it had to set in the west after the setting of the Two Vultures and before the setting of the First Two Crossbars of the Well Bucket (‘arquwata ad-dalw al-ulayan), which the calendar of Qushayr identifies as the last asterism of al-kharif. The name al-akhdar generally indicated a green color, sometimes bright and verdant, other times a dusty green or an intense black that tended toward green. Clear water was said to tend toward this color. When used to describe the night, al-akhdar indicated it was very dark.

The Auspicious Asterisms as lunar stations

For a brief description of the lunar stations, please see the Celestial Complexes section on the About page.

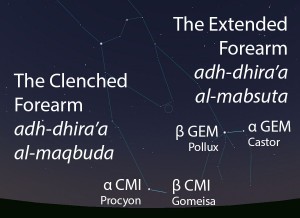

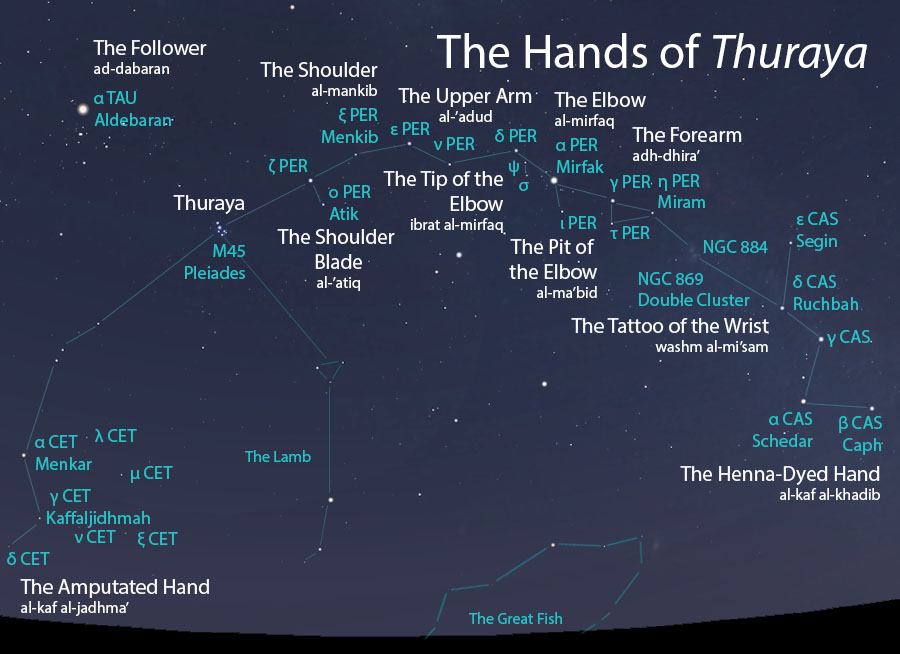

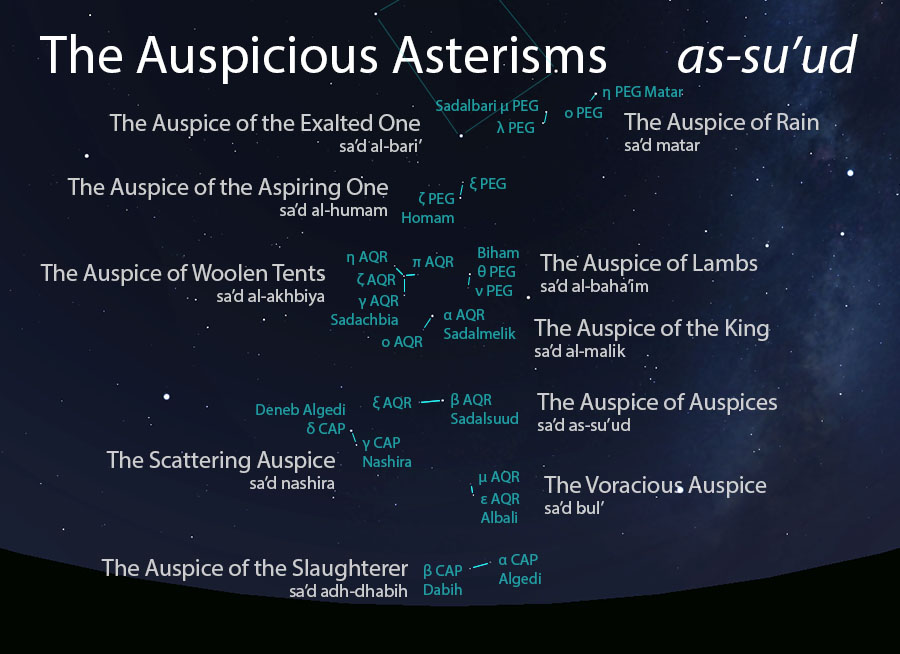

Because they are located so far to the north, the Two Vultures were not included in the calendar of lunar stations. Instead, the lunar stations continued with four of the ten Auspicious Asterisms (as-su’ud). The Arabic term indicates good fortune or something that is auspicious, especially a star. A celestial complex in its own right, the Auspicious Asterisms are all pairs of otherwise unremarkable stars, except for one that is comprised of four stars. All located within the same region of sky, the Auspicious Asterisms begin to set just before the Two Vultures set. When the calendar of lunar stations was generated, the pre-existing Auspicious Asterisms that were located closest to the Moon’s path were incorporated as lunar stations.

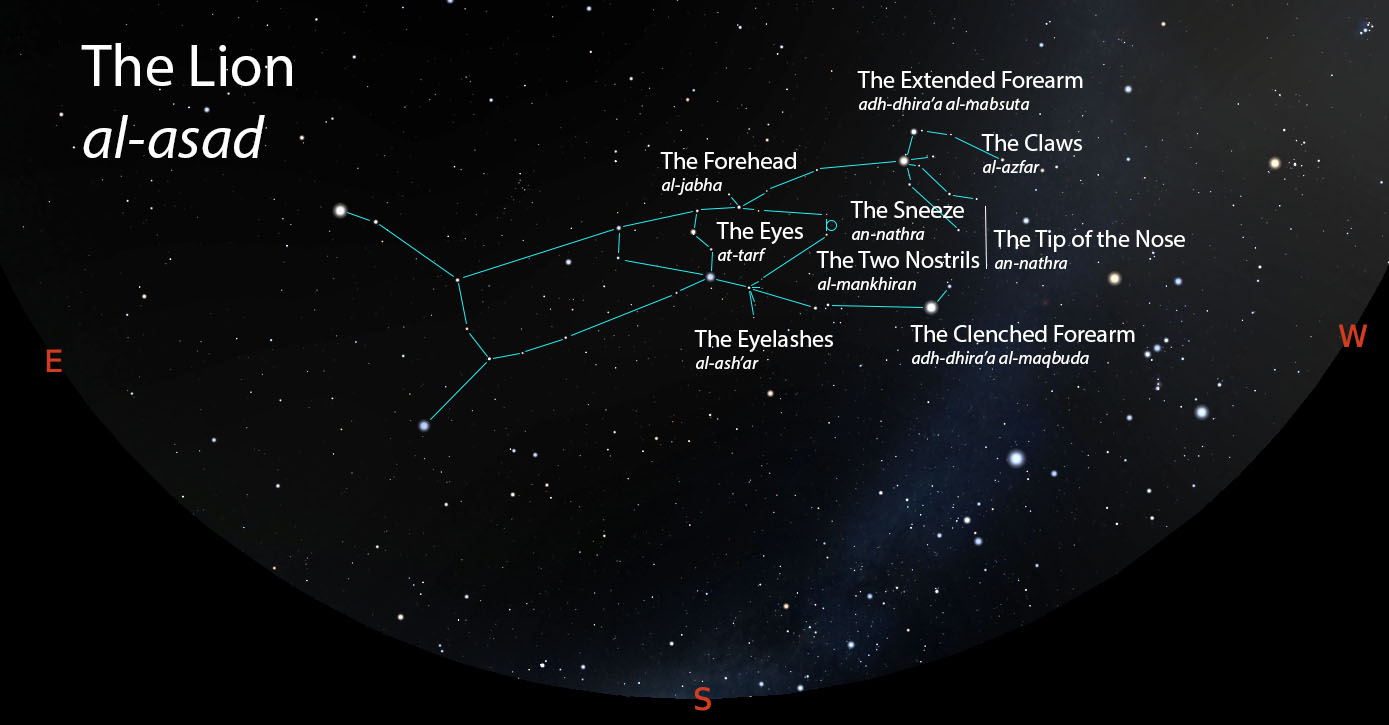

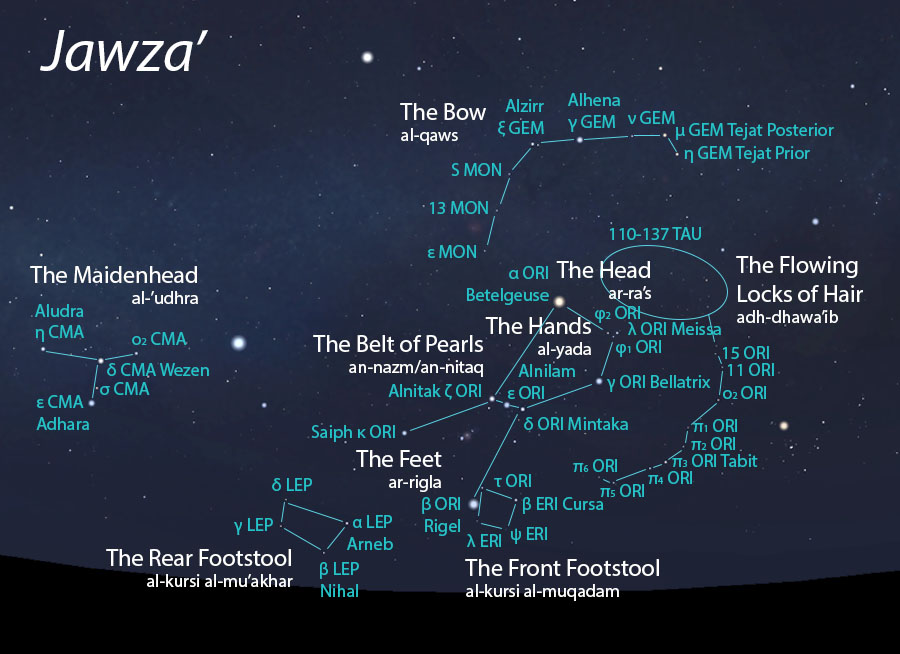

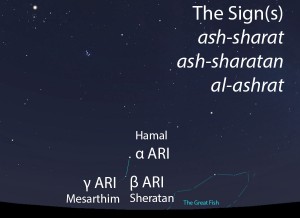

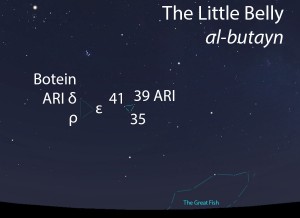

The Auspicious Asterisms (as-su’ud) as they appear setting in the west about 45 minutes before sunrise in early August. Sky simulations made with Stellarium.

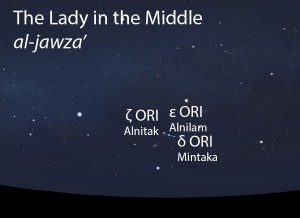

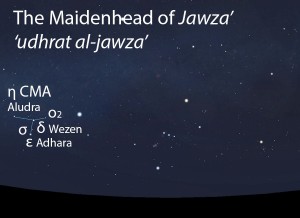

Continuing eastward from the 21st lunar station, the Wasteland (al-balda), the first Auspicious Asterism we encounter is the Auspice of the Slaughterer (sa’d adh-dhabih), a pair of stars that marked the 22nd lunar station. Very close to the northern star of the pair is a faint star that was called the Sheep (ash-shat), the one that is about to be slaughtered. It is this asterism that the 8th century poet at-Tirimah mentioned in the line of poetry above.

The 23rd lunar station was the Voracious Auspice (sa’d bula’), so called because it swallows everything. In this pair of stars, the western star is brighter than the eastern one, and so it was imagined to be moments away from swallowing the dimmer star and taking its light in the process.

The 24th lunar station was the Auspice of Auspices (sa’d as-su’ud), containing one of the brightest stars of the Auspicious Asterisms. The Auspice of Auspices was most sought after for good fortune among the ten Auspicious Asterisms, thus lending to its name. Ibn Qutuayba said the Auspice of Auspices was an asterism containing three stars, one bright and two dim, but most other accounts mentioned only two stars, one bright and one dim.

The final lunar station from among the Auspicious Asterisms was the Auspice of Woolen Tents (sa’d al-akhbiya). This asterism is the only one of the ten that contains more than two stars. The Auspice of Woolen Tents appears as a triangle of moderately bright stars with a fourth star located right in the center. The woolen tent (khiba’) for which the 25th lunar station was named was often made with 3 poles that met in the middle, a fitting description of the appearance of these stars in the sky.

Each of the lunar stations mentioned above is located along a line that parallels the path of the Moon through the sky. Following the Auspice of Woolen Tents, this line continues to the First Spout (al-fargh al-awal) of the Well Bucket (ad-dalw), which is where we began with the calendar of lunar stations a year ago.

The remaining six of the ten Auspicious Asterisms were not included in the calendar of lunar stations. The Scattering Auspice (sa’d nashira) was named for the wind that disburses the rain-bearing clouds or for the dry herbage that becomes green again during the rains at the end of the summer. The Auspice of the King (sa’d al-malik) included one of the brightest stars of the Auspicious Asterisms and was located between the Auspice of Auspices and the Auspice of Woolen Tents. The Auspice of Lambs (sa’d al-baha’im) followed a northerly track that took the remaining Auspicious Asterisms alongside the First Spout. The Auspice of the Aspiring One (sa’d al-humam), which referred to a magnanimous chief or king, and the Auspice of the Exalted One (sa’d al-bari’) each lay close to one of the two stars of the First Spout. The last of the group was the Auspice of Rain (sa’d matar), which set amid the setting of the Two Spouts that heralded the heavy marking rains (wasmi) of autumn.

The Vultures and Auspicious Asterisms still soar

Without Greek zodiacal constellations to break them up, the Two Vultures have survived into the lexicon of modern astronomy. The central bright stars of each of these asterisms bear names that derive from their specific Arabic names. Thus, the Flying Vulture (an-nasr at-ta’ir) survives in the star name Altair (α AQL), and the Alighting Vulture (an-nasr al-waqi’) survives as Vega (α LYR).

The Auspicious Asterisms are located in an area of sky that is now occupied by the Greek constellations Capricornus, Aquarius and Pegasus. Amazingly, every one of the ten Auspicious Asterisms endures in its original location, despite there being two zodiacal constellations in this area of sky. In Capricornus, one of the two bright stars of the Auspice of the Slaughterer (sa’d adh-dhabih) is called Dabih (β CAP), and even the sheep (ash-shat) that is about to be slaughtered is preserved in the star Alshat (ν CAP). On the other side of Capricornus, one of the stars of the Scattering Auspice (sa’d nashira) is called Nashira (γ CAP). In both of these cases, the other star of each pair bears a modern name that reflects the Arabic description of the Greek Goat, Capricornus: Algedi (α CAP), from the Arabic al-jady, “the kid,” and Deneb Algedi (δ CAP), “the tail of the kid” (deneb al-jady).

In Aquarius we find four more Auspicious Asterisms; in the first three of these, it is the brighter star that retains the name. The Voracious Auspice (sa’d bula’) bears an accurate but alternate name, Albali (ε AQR). Next are the Auspice of Auspices (sa’d as-su’ud), Sadalsuud (β AQR), and the Auspice of the King (sa’d al-malik), Sadalmelik (α AQR). Of the fours stars that comprise the Auspice of Woolen Tents (sa’d al-akhbiya), only the brightest bears a modern name: Sadachbia (γ AQR).

The remaining four Auspicious Asterisms lie in modern-day Pegasus. Because these asterisms were relatively dimmer and lay outside the Square of Pegasus (the ancient Well Bucket, ad-dalw), they were not displaced with other star names. Here, we find the Auspice of Lambs (sa’d al-baha’im) as Biham (θ PEG), which is derived from the alternate grammatical form (sa’d al-biham). There is also the Auspice of the Aspiring One (sa’d al-humam), Homam (ζ PEG), the Auspice of the Exalted One (sa’d al-bari’), Sadalbari (μ PEG), and the Auspice of Rain (sa’d matar), Matar (η PEG).

The Auspicious Asterisms have truly lived up to their name, for each one of them has had the good fortune of enduring to the present day in modern depictions of the night sky. It is these stars that lead us back to the Well Bucket as this year ends and the next begins. Thus we complete our year-long journey through two Arabian star calendars. Stay tuned for more to come in the next year.

What’s next?

Please leave a comment below, and tell me about your observations of the Ostriches. Be sure to include your city and state/country so we can see how the timings vary by location.

Star Catalog Entries for this Celestial Complex

The Two Vultures Celestial Complex (an-nasran, النسران)

The Alighting Vulture (an-nasr al-waqi’, النسر الواقع)

The Flying Vulture (an-nasr at-ta’ir, النسر الطائر)

The Auspicious Asterisms Celestial Complex (as-su’ud, السعود)

The Auspice of the Slaughterer (sa’d adh-dhabih, سعد الذابح)

The Sheep (ash-shat, الشاة)

The Voracious Auspice (sa’d bul’, سعد بلع)

The Scattering Auspice (sa’d nashira, سعد ناشرة)

The Auspice of Auspices (sa’d as-su’ud, سعد السعود)

The Auspice of the King (sa’d al-malik, سعد الملك)

The Auspice of Lambs (sa’d al-baha’im, سعد البهائم)

The Auspice of Woolen Tents (sa’d al-akhbiya, سعد الأخبية)

The Auspice of the Aspiring One (sa’d al-humam, سعد الهمام)

The Auspice of the Exalted One (sa’d al-bari’, سعد البارع)

The Auspice of Rain (sa’d matar, سعد مطر)

Click here to go to the full star catalog (a work in progress).