Feature image by Alexander Vasenin CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the US, we say that March comes in like a lion and goes out like a lamb. This saying may reference the rising of the Greek constellation of Leo in the east during sunset at the beginning of April, and the setting of Aries in the west after sunset at the end of the month.

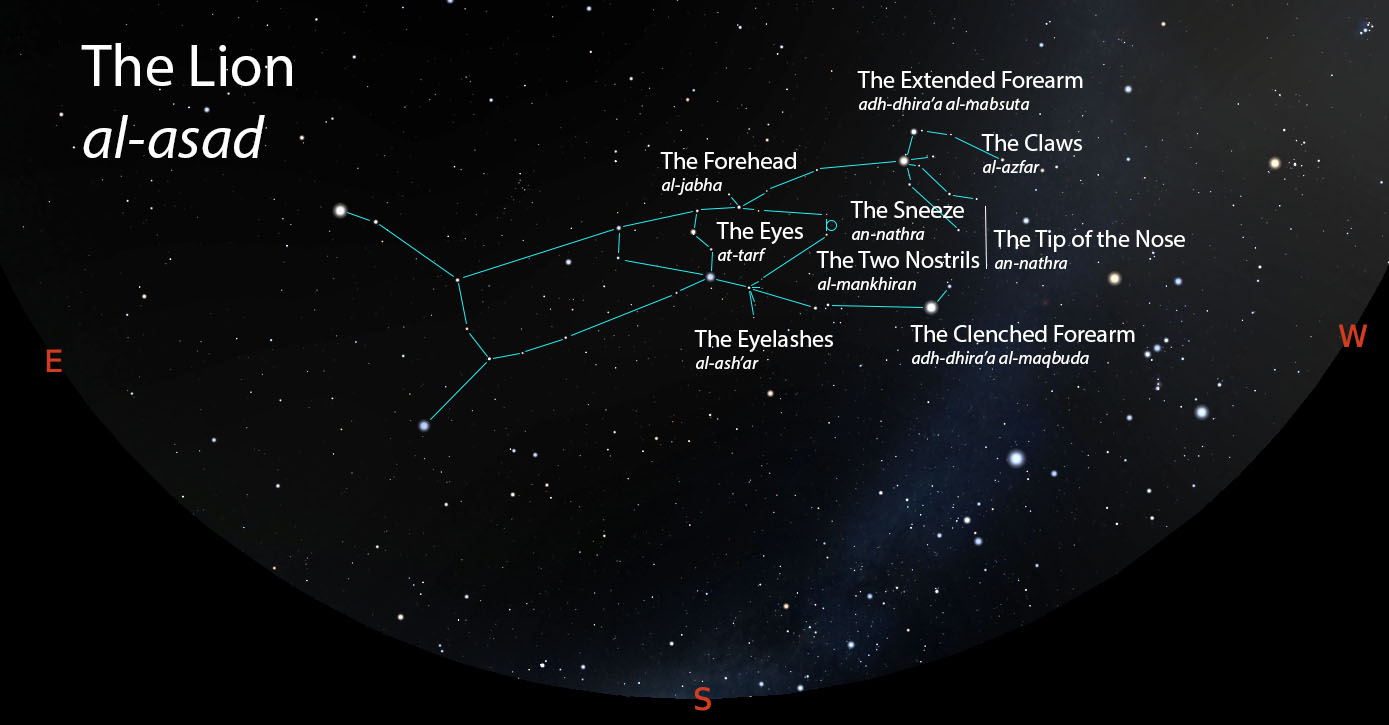

In contrast to this, the Lion (al-asad) of ancient Arabia was so massive that it roared from January to May, stretching across three seasons in its pre-dawn stellar settings, according to the rain star calendar of Qushayr. The 8th century poet Dhu ar-Rumma addressed the protracted seasonal girth of the Lion by referring to it in the plural.

جدا قضة الآساد

…with good fortune at the dawn setting of the Lions…Dhu ar-Rumma

735 C.E.

Previously, we saw Jawza’ herald the onset of winter (ash-shatawi). This cold season continues with the setting of the Two Forearms (adh-dhira’an) and then the Nose of the Lion (nathrat al-asad). The setting of the Forehead of the Lion (jabhat al-asad) marks the end of winter and the onset of the warm spring rains (ad-dafa’i). Some weeks later, the Two Shanks of the Lion (saqa ‘l-asad) set about 40 days apart, defining between them the rainy portion of the summer (as-sayf). All of this seasonal rain activity unfolds over the course of about four months, between the morning settings of the two brilliant pairs of stars (its Two Forearms and its Two Shanks) that roughly define the boundaries of the Lion.

الأسد

How to observe the Lion

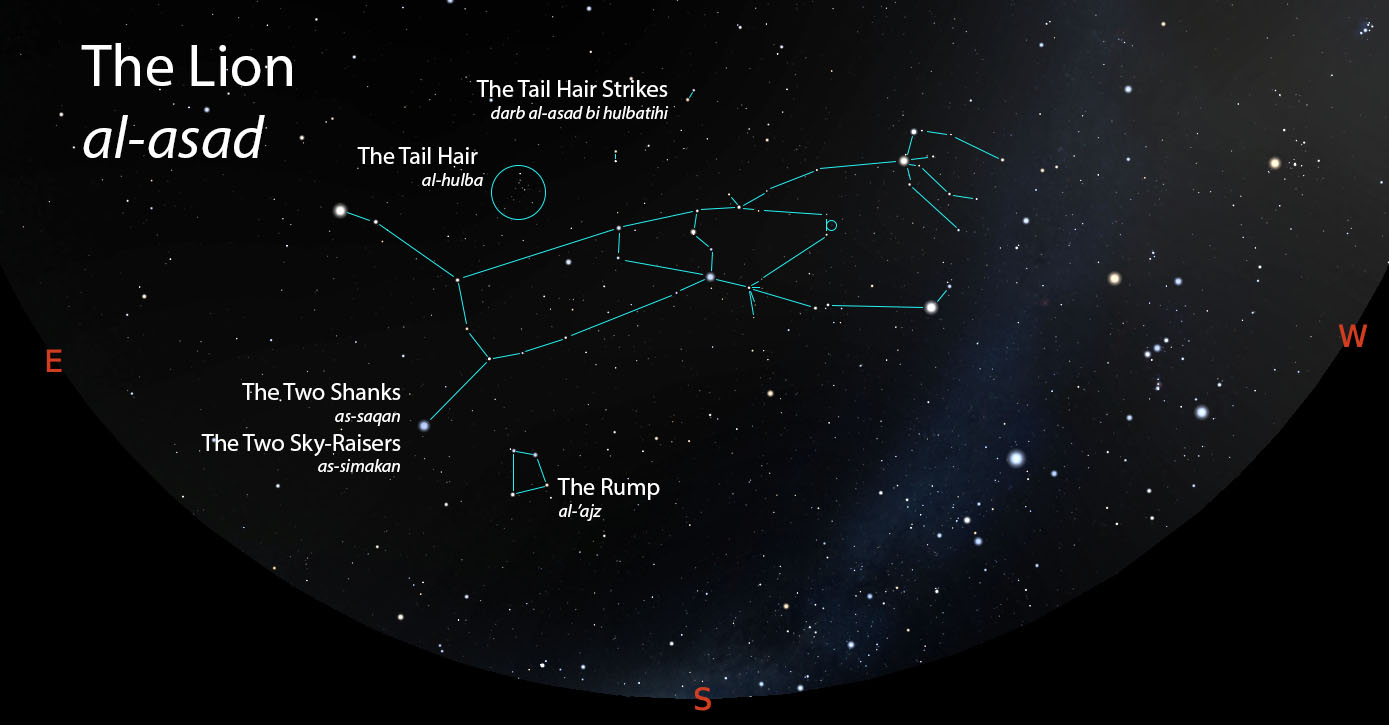

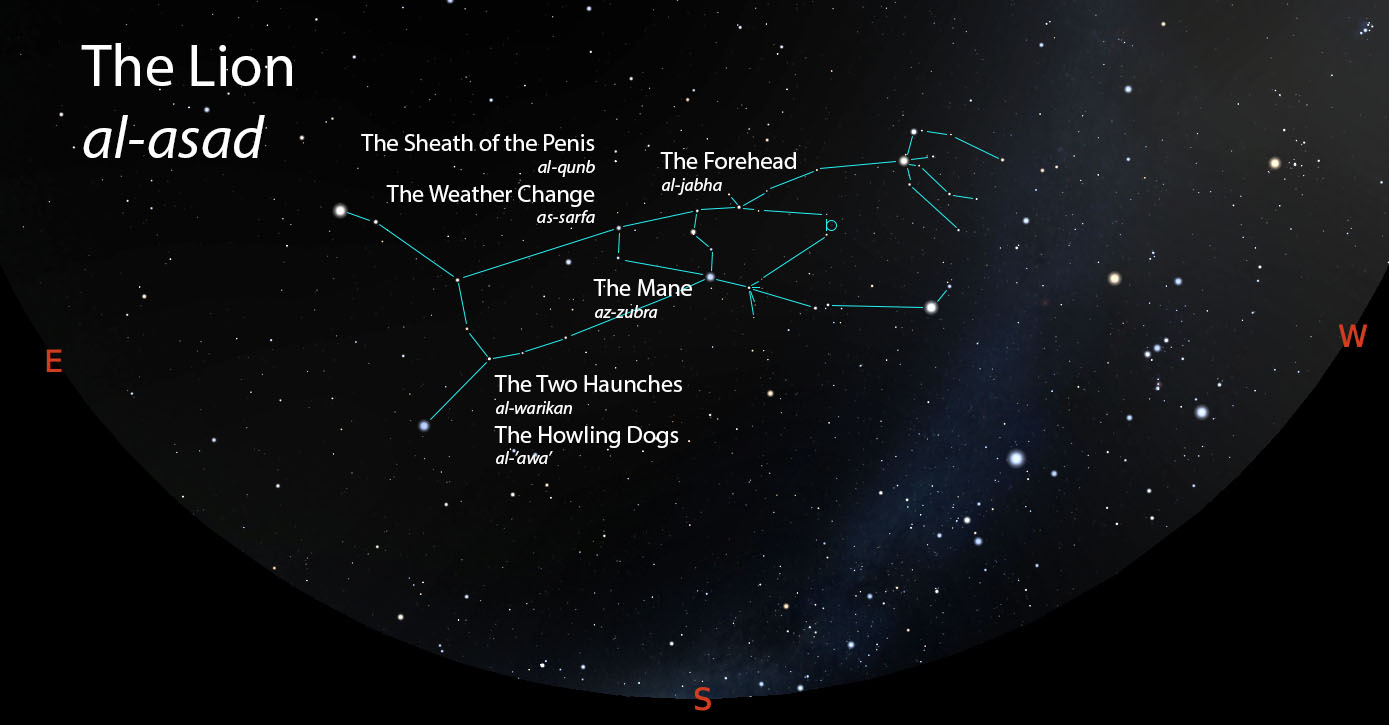

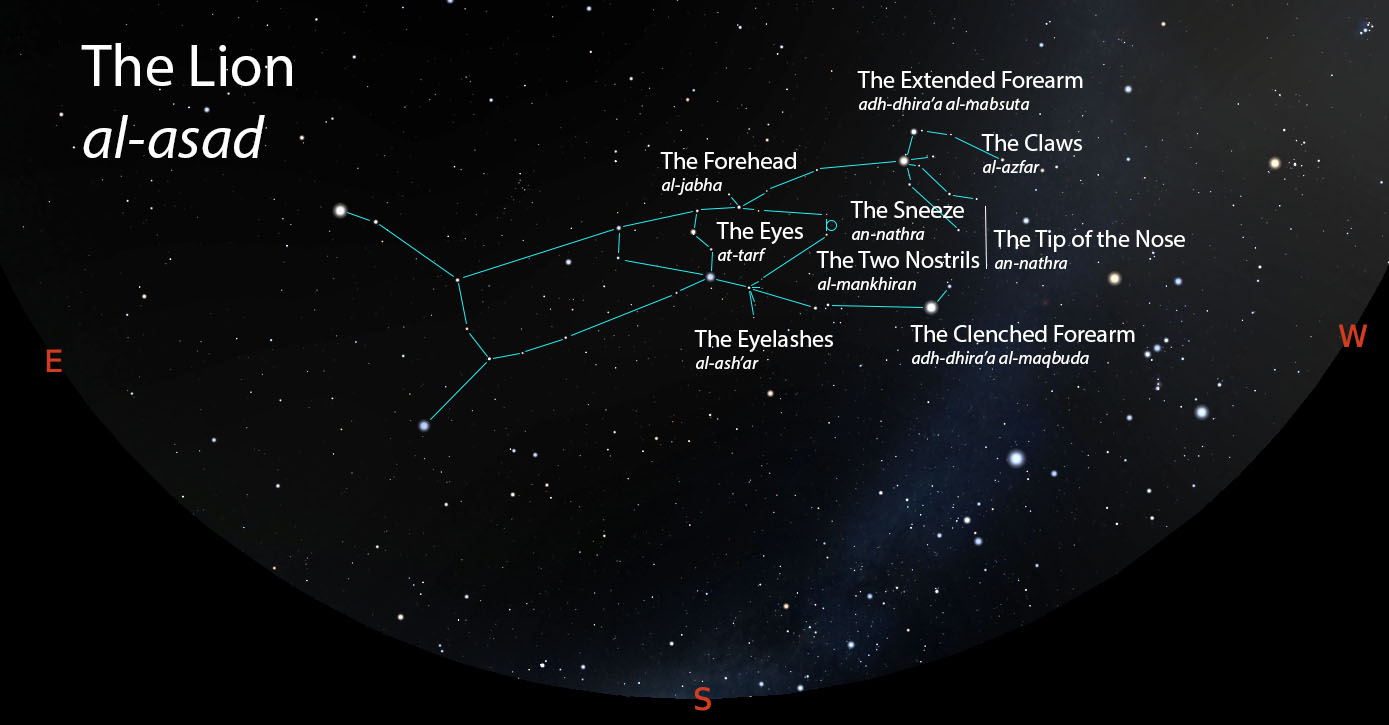

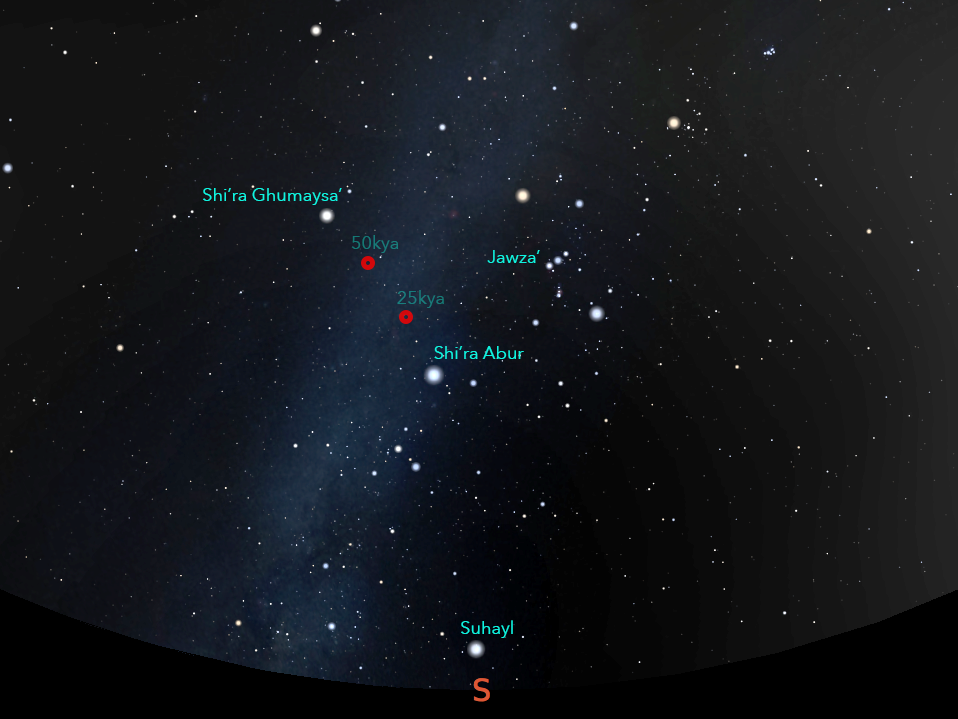

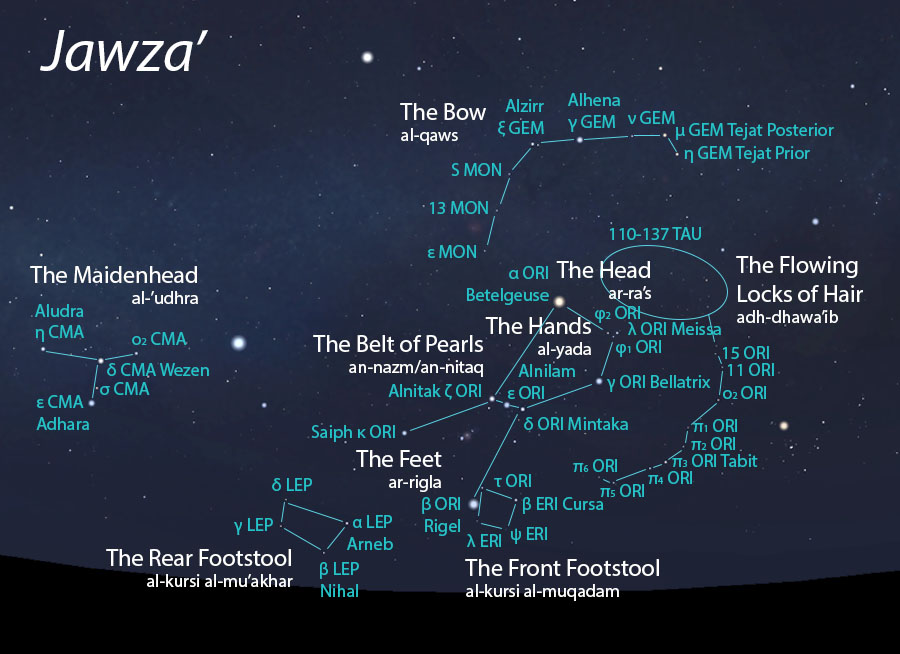

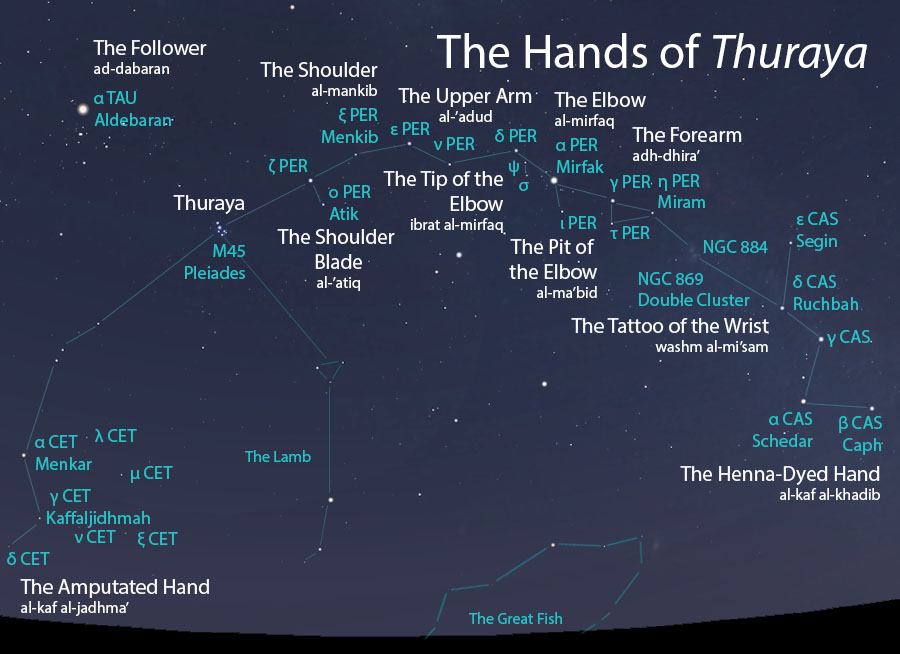

When the whole Lion was above the horizon, it nearly covered the sky from west to east as it consumed some 135 angular degrees of the sky. In order to present this entire figure, the locator map below has a much larger scale than usual.

Wide-field view of the Lion (al-asad) and its elements as they appear when its Forehead (al-jabha) is in the middle of the sky. Sky simulations made with Stellarium.

The proper time to observe a star’s morning setting (or rising) is called ghalas in Arabic, at time when the darkness of night mixes with the white and red light of dawn in the tracts of the horizon (How to Observe). Look to the western horizon about 45 minutes before your local sunrise (times available at timeanddate.com). To spot the magnificent Lion, first find its Two Forearms as they prepare to sink below the western horizon (see next star map below). Each forearm consists of a pair of stars located next to each other parallel to the horizon. The Clenched Forearm sets first, and at this time the other Extended Forearm is located to the right and above it. Located directly above the Clenched Forearm, at a level slightly higher then the Extended Forearm to the right, lies the Nose of the Lion, an unremarkable pair of stars located next to a large but dim star cluster. The remaining elements follow these stars high into the sky through the zenith to the upper parts of the southeastern sky.

الذراعان ونثرتهما والجبهة

The Two Forearms and the Forehead as rain stars

For a brief description of the rain stars, please see the Celestial Complexes section on the About page.

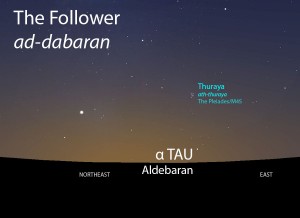

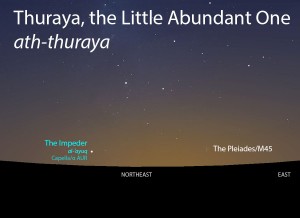

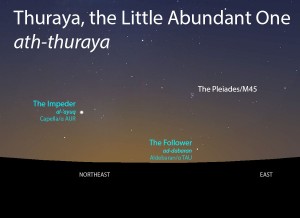

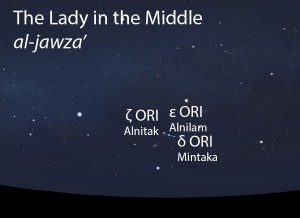

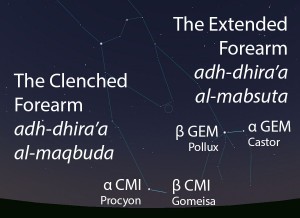

The Two Forearms and the Nose (adh-dhira’an wa’n-nathra) as they appear setting in the west about 45 minutes before sunrise in early January.

In the rain star calendar of Qushayr, the second asterism of the winter rainy season (ash-shatawi) is the Two Forearms (adh-dhira’an) of the Lion, along with the Tip of the Nose (an-nathra). Each Forearm is marked by a pair of bright stars, which makes for a good rain star asterism that is visible in the growing light of dawn. The Two Forearms set about two weeks apart, and one or both could be mentioned in the context of bringing rain. We’ve already run into the first pair to set: the brighter star in this pair is the Little Bleary-Eyed Shi’ra from the legend of Jawza’.

As rain stars, the Two Forearms were said to never break their promise. Even if there had been no rain in the year prior to their setting, the Forearms would certainly bring at least a weak rain. The following line of poetry describes a deluge of rain at the setting of one of the Forearms.

وأردفت الذراع لها بنوء سجوم الماء فانسجل انسجالا

The Forearm made to follow behind it

a rain period pouring forth much water,

and so it poured out a continuous flow of water.Dhu ar-Rumma

735 C.E.

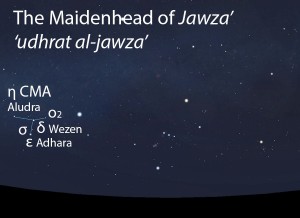

The Tip of the Nose (an-nathra) consisted of a pair of faint stars that lies close to a large but dim star cluster. This is one of those times when English translation fails to communicate the full meaning of an Arabic word. The related verb nathara means “to scatter” or “to disperse,” so the noun an-nathra in its basic sense indicates “a scattering.” For obvious reasons, this word also came to indicate a sneeze, and by extension the tip of the nose, the place from which the sneeze originates. This is precisely what the Arabs saw in the Tip of the Nose, a pair of dim stars that appear to have sneezed out the star cluster, which on account of its dimness appears as a fuzzy blotch in the sky. More explicitly, some Arabs saw the two stars of the Tip of the Nose as the Two Nostrils (al-mankhiran) and the star cluster alone as the Sneeze (an-nathra). As an asterism, the Tip of the Nose was well-known but too faint to be visible in the growing light of dawn. As such, it could not function as a rain star on its own but instead was mentioned along with the Two Forearms.

The Forehead (al-jabha) as it appears in the west about 45 minutes before sunrise in early January.

Setting about a month after the second Forearm set, the four stars of the Forehead (al-jabha) marked the end of winter and the beginning of the warmer rainy season of spring (ad-dafa’i). More specifically, the first pair of stars from the Forehead that set marked the end of winter, and the second pair that set about a week later brought the onset of spring. At the setting of the Forehead, the brink of winter was broken, and new life began as the wind spread pollen around. Trees sprouted their leaves, truffles grew in central Arabia and every river valley appeared to fill with pasture. Also during this time, camels bore their young, and it was said, “If it were not for the rain period of the Forehead, the Arabs would not have camels.”

We will encounter more rain stars that belong to the Lion when we discover the warm spring rains in the next post.

الذراعة المبسوطة والنثرة والطرف والجبهة

The Extended Forearm and following as lunar stations

For a brief description of the lunar stations, please see the Celestial Complexes section on the About page.

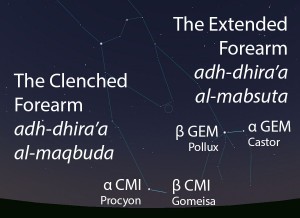

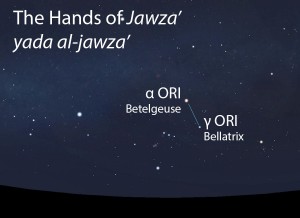

The calendar of the lunar stations also included the Forearms, the Tip of the Nose and the Forehead, but with some significant differences. At some point, the Two Forearms were differentiated by the Arabs as the Clenched Forearm (adh-dhira’ al-maqbuda) and the Extended Forearm (adh-dhira’ al-mabsuta). The Clenched Forearm was the first pair to set and included the star that designated the Little Bleary-Eyed One (ash-shi’ra al-ghumaysa’). When a cat, whether wild or domestic, reaches it forearm outward to grab something, it often bares its claws. Likewise, the Extended Forearm of the Lion has lines of stars that radiate from it, and these were seen as the Claws (al-azfar) of the outstretched Forearm.

The Extended Forearm (adh-dhira’ al-mabsuta) and the Clenched Forearm (adh-dhira’ al-maqbuda) as they appear setting in the west about 45 minutes before sunrise in early January.

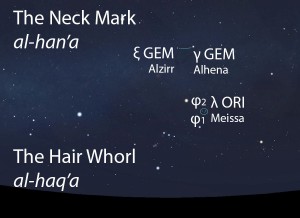

Although the ecliptic (the path of the Moon against the stellar background) passes more or less right between the two pairs of stars that made up the Two Forearms, the Moon comes somewhat closer to the Extended Forearm, and so within the context of the lunar stations only it, and not the Clenched Forearm, had the honor of being a lunar station. Often simply called the Forearm (adh-dhira’), the Extended Forearm was the seventh lunar station, following in the tracks of the Neck Mark (al-han’a).

The Tip of the Nose was then the eighth lunar station, and herein is another distinction. In the rain star calendar, the Two Forearms were the bright stars that the Arabs relied upon for observing their pre-dawn settings. The Tip of the Nose was always following closely behind, but it was too dim for use as a rain star on its own. In the calendar of lunar stations, the Tip of the Nose has its own status as a lunar station separately from the Forearm. The reinforces the idea that the calendar of lunar stations was more a conceptual calendar than a practical one.

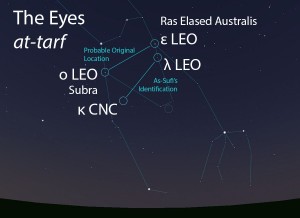

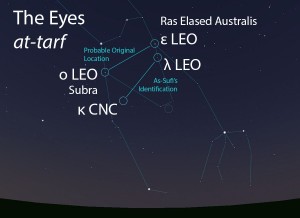

The Eyes (at-tarf) as they appear in the west about 45 minutes before sunrise in early January.

Following the Tip of the Nose is another pair of comparatively dimmer stars that made up the ninth lunar station, the Eyes (at-tarf). The identification of these stars has historically been rather problematic. Their description in the earliest surviving record is by Ibn Qutayba (d. 889), who says that these two stars are located right in front of the Forehead. He also says that many stars called the Eyelashes (al-ash’ar) are located in front of the Eyes. Considering the well-estabished locations of the Tip of the Nose and the Forehead in the sky, the most likely candidates for the Eyes are two stars that lie in front of the first and last Forehead stars and are comparable in brightness. There are several fainter stars in front of each of these two stars that would fit the description of the Hairs, indicating the Lion’s eyelashes. A century after Ibn Qutayba, as-Sufi identified the Eyes as a pair of faint stars that are located in front of the brighter stars that I just identified, and this identification has stuck ever since. It is possible that the brighter stars were originally identified as the Eyes but moved to the dimmer stars to be located closer to the midpoint between the Tip of the Nose and the Forehead.

The Forehead (al-jabha) then followed the Eyes as the tenth lunar station. As we enter the season of warm spring rains (ad-dafa’i) in the next post, we will see more elements of the Lion functioning as lunar stations.

الأسد

Roars of the Mesopotamian-Greek Lion

You may have seen in the Forehead of the Lion the familiar shape of the head of the Greek constellation Leo, also a lion. The Greek Leo is a much smaller stellar picture of a lion that they adopted from Babylonian astronomy. This lion likely dates back to 3rd or 4th millennium BCE Mesopotamia. In this depiction, the top of the Arab Forehead is the head of the lion, and the bright star at the bottom of the Forehead is its heart. It is possible, but by no means certain, that the Arabian Lion literally grew out of this Mesopotamian tradition long ago, extending both its Forearms and its hindquarters to attain its massive size.

When Greek astronomical texts were translated into Arabic, the stars of the Arabian Lion were realigned with the smaller Mesopotamian-Greek figure of the lion. Today’s modern star names for the bright stars of Leo derive largely from the Arabic descriptions of the Greek Leo. For example, the two stars Ras Elased Borealis (μ LEO) and Ras Elased Australis (ε LEO) come from the Arabic ra’s al-asad “the head of the lion,” designating the top of the head in the Mesopotamian-Greek figure. An exception to this is Algieba (γ LEO), one of the stars located in the Forehead whose name derives from the Arabic al-jabha. Some modern star charts also identify one of Leo’s stars as Alterf (λ LEO); ironically, this is not the location of one of the two stars that as-Sufi identified as the Eyes (at-tarf), but it is the more likely location of the northern star of the Eyes identified above.

What of the Two Forearms and the Tip of the Nose? Two stars in the Greek constellation of Gemini were arbitrarily named Mebsuta (ε GEM), from adh-dhira’ al-mabsuta, and Mekbuda (ζ GEM), from adh-dhira’ al-maqbuda. These, of course, are not the original locations of either of the Two Forearms, although these stars did belong to the Claws (al-azfar) of the Extended Forearm. Nothing remains of the Tip of the Nose in modern astronomy, as the formation was seen by the Romans as a pair of donkeys next to a manger (praesepe in Latin). This picture remains today in the internationally recognized star names of Asellus Borealis (γ CNC, “the Northern Donkey”), Asellus Australis (δ CNC, “the Southern Donkey”) and Praesepe (“the Manger”) for the star cluster.

Much as Asiatic lions are now endangered today, and their populations greatly diminished, so has the once enormous Arabian Lion been reduced to a diminutive Greek lion cub.

What’s next?

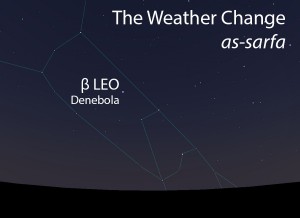

Next time, we continue with the megaconstellation of the Lion and a significant shift to warmer weather.

In the meantime, I’d love to hear from you! Please leave a comment below, and tell me about your observations of these ancient asterisms. Be sure to include your city and state/country so we can see how the timings vary by location.

Star Catalog Entries for this Celestial Complex

The Lion Celestial Complex (al-asad, الأسد)

The Two Forearms (adh-dhira’an, الذراعان)

The Clenched Forearm (adh-dhira’a al-maqbuda, الذراعة المقبوضة)

The Extended Forearm (adh-dhira’a al-mabsuta, الذراعة المبسوطة)

The Claws (al-azfar, الأظفار)

The Tip of the Nose (an-nathra, النثرة)

The Two Nostrils (al-mankhiran, المنخران)

The Sneeze (an-nathra, النثرة)

The Eyes (at-tarf, الطرف)

The Eyelashes (al-ash’ar, الأشعار)

The Forehead (al-jabha, الجبهة)

Click here to go to the full star catalog (a work in progress).