The Little Lamb that Changed the Calendar

Feature image by Ed Brambley CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The heavy autumnal rains continue this week with the setting of the Arabian constellation of the Lamb (al-hamal). But this lamb is a bit rambunctious, and he ends up shifting the entire Arab star calendar by a month. In this post, we pick up our second asterism of the rain star calendar shared by the Arab tribes of Qushayr and Qays, as well as two more lunar stations.

جاد لها بالدبل الوسمي من باكر الأشراط أشراطي

من الثريا انقض أو دلوي

The autumnal marking rain

fell abundantly upon the land in large drops,

from the first seasonal rain of the Signs

a rain that darted down from the stars of Thuraya,

or else a rain of the Well Bucket.Al-‘Ajaj,

7th/8th century C.E.

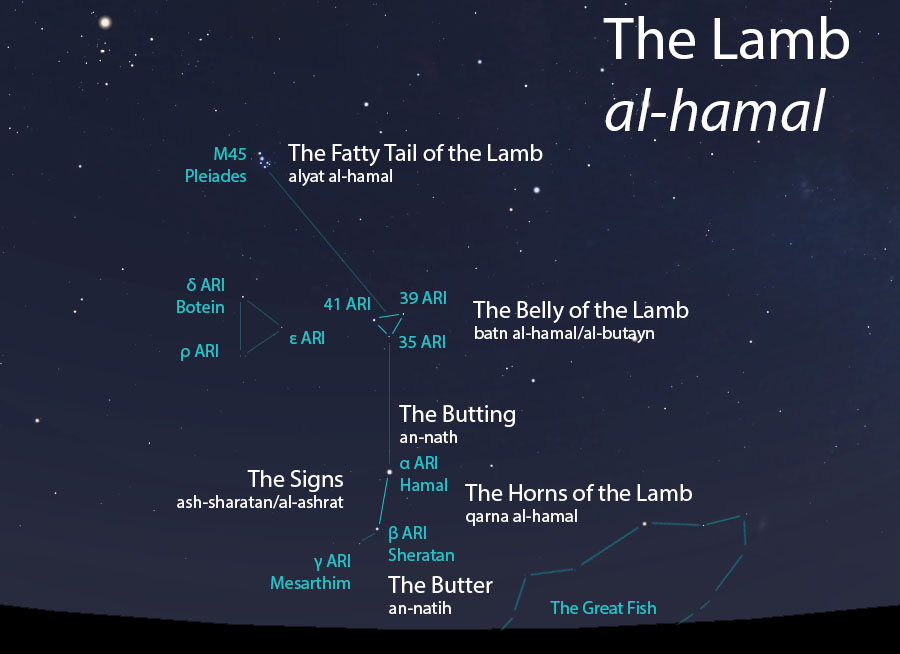

The poetry again relates this celestial complex back to the Well Bucket (ad-dalw). The Arabic term hamal refers to a first-year lamb, and this one in particular is of the fat-tailed sheep variety, perhaps an Awassi lamb like the one pictured above. These sheep were bred for their large fatty rumps and tails. The stars known as the Signs (al-ashrat in the poetry above) also mark the little horns of the Lamb, and its fatty tail is marked by the star cluster called Thuraya.

How to observe the Lamb

The Lamb (al-hamal) as it appears setting in the west about 45 minutes before sunrise in mid-November. Sky simulations made with Stellarium.

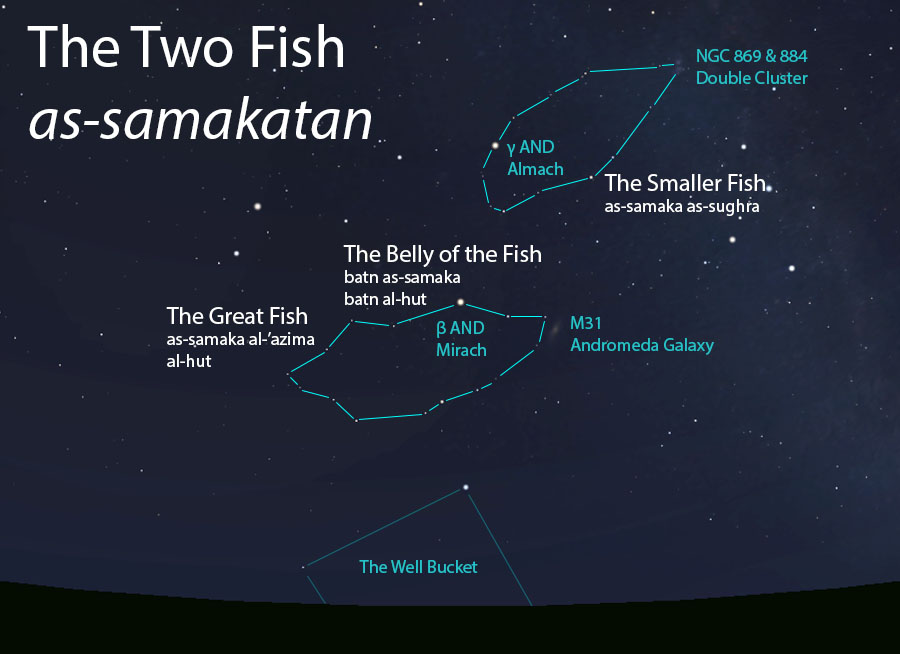

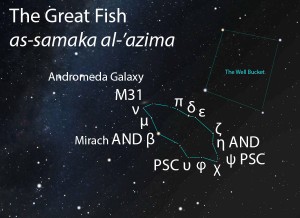

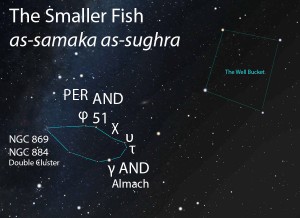

The proper time to observe a star’s morning setting (or rising) is called ghalas in Arabic, at time when the darkness of night mixes with the white and red light of dawn in the tracts of the horizon (How to Observe). Look to the western horizon about 45 minutes before your local sunrise (times available at timeanddate.com). The Two Horns of the Lamb (qarna al-hamal) will appear as two somewhat bright stars located directly to the left of the Belly of the Great Fish (batn al-hut). These two stars were also called the Butting and the Butter (an-nath w’an-natih), and their rising in the morning was regarded as inauspicious. The figure of the Lamb continues up the sky through its Belly (batn al-hamal) to its fatty tail (alyat al-hamal), marked by the Pleiades star cluster.

Image of a young Awassi lamb photographed by Ed Brambley CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

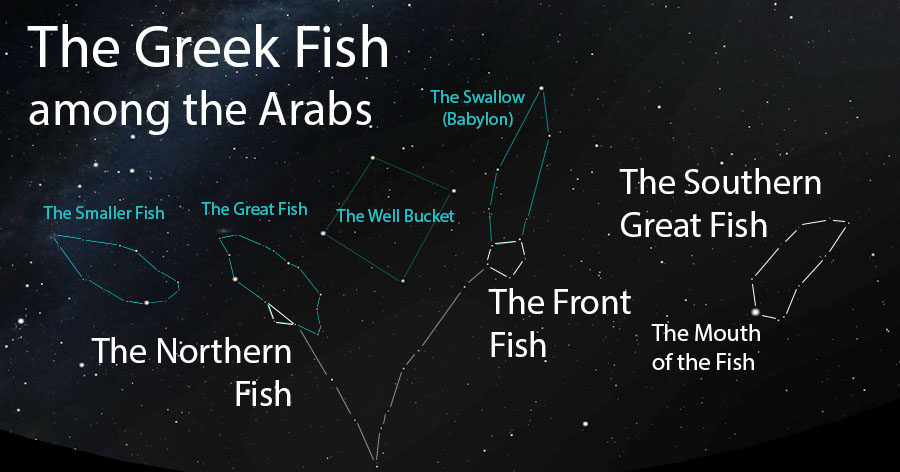

This image of the Lamb in Arabia was rather different than the Greek image of the Ram (Aries), which itself was derived from a Babylonian asterism. The Babylonian asterism was originally depicted as a farmhand, but during the first millennium BCE it was elevated to the status of a zodiacal constellation to help flesh out the intended complement of 12 constellations. During this time, the vernal equinox (the point in space where the plane of the earth’s orbit intersects the earth’s equator projected into space) came to rest in this constellation. Its new status as the first constellation of the solar year may have led to its being honored with the divine symbol of the ram. This symbolism was adopted by the Greeks as Aries, and they called the vernal equinox the First Point of Aries. The Babylonian/Greek figure of Aries does not have a fleshy tail, and only one of the Arabian Horn stars lay on one of the curved ram’s horns.

The Signs as rain stars

For a brief description of the rain stars, please see the Celestial Complexes section on the About page.

The Signs (al-ashrat/ash-sharatan) as they appear setting in the west about 45 minutes before sunrise in early November. Sky simulations made with Stellarium.

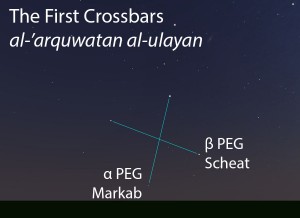

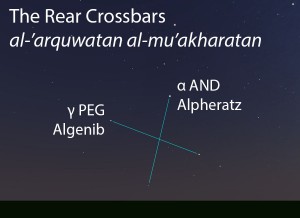

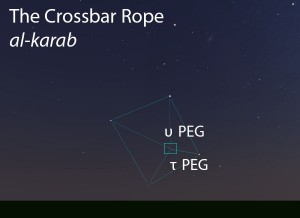

Our first post reported the beginning of the calendar of rains stars in what would have been late September some 1200 years ago. The coming of the wasmi “marking” rains was heralded by the pre-dawn setting of the Rear Two Crossbars of the Bucket (al-‘arquwatan al-mu’akharatan min ad-dalw). This week, the second entry in the rain star calendar, and still within the season of al-wasmi, is the Sign (ash-sharat), an asterism whose meaning is unclear. Authors writing in the 9th century CE attribute this to the fact that the sun began its new year in this asterism, so it served as a sign of the new year. This is true, but the first translations of Greek astronomy occurred after this asterism’s early appearances in poetry, which usually employed the plural form, al-ashrat (the Signs). It is possible that earlier Babylonian encounters introduced the Arabs to this name and its solar significance even before Islam. However, it is equally likely that the name had some other meaning that has since been lost to the ravages of history.

In most of the poetic references, including the earliest ones, this asterism is named in its plural form, al-ashrat (the Signs). In Arabic, this term is reserved for plurals of three or more, and so this term connoted the pair of bright Horn stars together with the somewhat dimer star that lies very close to them. In the rain star calendar, it is the singular term ash-sharat that is used, connoting the group of stars as a whole: “the Sign (of the stars)”. Although the Two Horns set in the west one after the other, about 5-6 days apart, they did rise together in the east. As we have seen already in al-farghan (the Two Spouts), al-‘arquwatan (the Two Crossbars) and qarna al-hamal (the Two Horns of the Lamb), pairs of stars were especially significant for many Arabs. Within the context of the Signs, the two Horn stars came to be called ash-sharatan (the Two Signs). This dual designation appears to have come into greater usage after the Arab adaptation of the Indian lunar stations.

The Two Signs and the Little Belly as lunar stations

For a brief description of the lunar stations, please see the Celestial Complexes section on the About page.

Within the celestial complex of the lunar stations, the asterism of the Signs is always mentioned using the dual form ash-sharatan and never the singular ash-sharat or plural forms al-ashrat. In the account of Qutrub (died 821 CE), the Two Signs is listed as the third lunar station, following the Second Spout and the Great Fish. This matches the rain star calendar, which started its year with the Rear Crossbars, which use the same stars as the Second Spout. However, by the time of Ibn Qutayba (died 889), the organization of the lunar stations had shifted to recognize that the Two Signs was the location of the vernal equinox, and so he begins the listing of the lunar stations with the Two Signs. All subsequent listings follow this arrangement. This tells us that there was approximately a 4-week forward adjustment of the calendar that occurred sometime during the 9th century CE. This timing would have followed about half a century or more of Arabic translations of Greek astronomical texts, including the work of Hipparchus, who first defined the First Point of Aries.

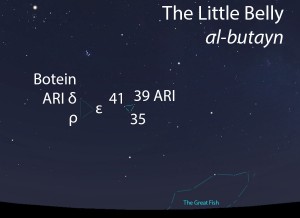

The Little Belly (al-butayn) as it appears in the west about 45 minutes before sunrise in mid-November. Sky simulations made with Stellarium.

Although the “new” first lunar station of the Two Signs did not directly invoke the Lamb, the second station was its Belly (batn al-hamal). As a lunar station, this asterism received a special diminutive name, the Little Belly (al-butayn). This tight grouping of three stars was said to resemble the three trivet stones (athafi) that would hold a cooking pot above the fire. Over the centuries, it has had two competing identifications in the sky. The first, and most likely in my opinion, was the trio 35, 39 and 41 ARI, the latter of which is the brightest star that lies between the Two Horns and the Fatty Tail of the Lamb. These three stars form a moderately bright, closely grouped equilateral triangle. This was the identification favored by Ibn Qutayba. However, al-Sufi favored a dimmer, wider trio of stars because they were located closer to the path of the moon through the sky: δ, ε and ρ ARI. Functionally, this second grouping is too dim to be seen through the morning twilight and therefore cannot have properly functioned as calendrical stars of this type.

The Fatty Tail of the Lamb (alyat al-hamal) also functioned as a lunar station, as well as a rain star. However, that story will have to wait for next time because its significance within Arab culture deserves its own blog post.

Lamb stars amidst the Greek constellations

In my post about the Well Bucket, we saw its name given to modern-day Aquarius and its constituent star names scattered to the winds. Then, we saw a similar fate befall the Great Fish, whose name was given to modern-day Pisces. This time, the story is different. Although the interpreted figures of the Arab Lamb and the Babylonian/Greek Ram differed somewhat, they had much more in common. Therefore, whatever the origins for the larger Arab Lamb may have been, its conversion to the Greek Ram left most of its original star names intact. The term al-hamal is still used by Arabs today to describe what is now the Greek image of Aries, and so the little Lamb has become a full-grown Ram.

Remarkably, even the modern-day internationally recognized star names within Aries are in their proper positions. The brightest star in modern-day Aries is called Hamal (“the Lamb”). The second brightest one is called Sheratan (“the Two Signs”). Together, these two stars are the very stars that comprised the Two Signs or the Two Horns of the Lamb. The third star of the Signs (as al-ashrat) is today called Mesarthim, which was the result of ash-sharatan being corrupted and erroneously then to be the Hebrew word for “servants.” Its location, however, was correctly applied. The Little Belly has also survived as the modern star name, Botein (from al-butayn). It was applied to the brightest star of the alternative, dimmer trio of stars, δ ARI.

Al-nath (the Butting) also survives as the star name Elnath, but it was transferred to one of the horns in the Greek image of Taurus, the Bull. At least it still gets to do the butting, albeit with a much larger horn.

What’s next?

The next post will introduce you to the greatest star grouping in Arab astronomy, past and present. It was so significant to the Arabs throughout the centuries that they often called it simply “the Asterism.”

In the meantime, I’d love to hear from you! Please leave a comment below, and tell me about your observations of these ancient asterisms. Be sure to include your city and state/country so we can see how the timings vary by location.

Star Catalog Entries for this Celestial Complex

The Lamb Complex (al-hamal, الحمل)

The Two Signs (ash-sharatan, الشرطان)

The Horns of the Lamb (qarna al-hamal, قرنا الحمل)

The Little Belly of the Lamb (al-butayn, البطين)

The Fatty Tail of the Lamb (alyat al-hamal, ألية الحمل)

Click here to go to the full star catalog (a work in progress).